00:00

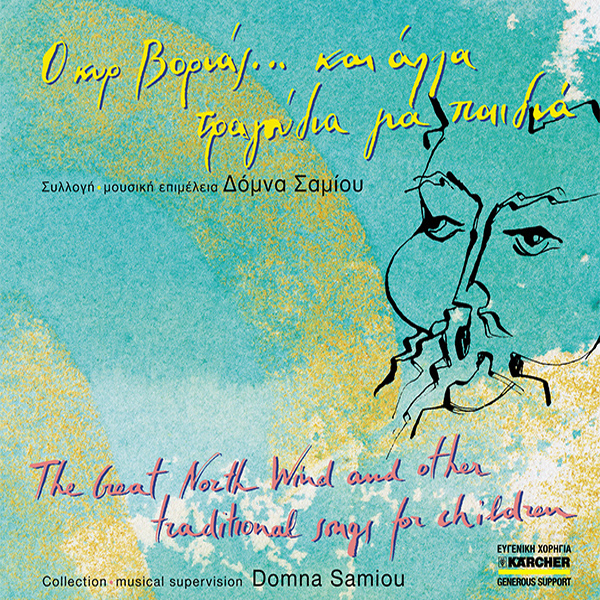

Home / Her Work / Discography / The Great North Wind and Other Traditional Songs for Children

‘The Great North Wind ….’ is Domna Samiou’s second CD dedicated to her ‘young friends’. One of Domna’s main concerns is that, unless children are initiated in music, these songs will gradually disappear as time goes by. This CD is a good companion to those who want to offer their children a hint of a different magical world.

I grew up in a very different world, and was fortunate enough to learn so many of the thousands of songs I know first from my parents and then from my teacher, Simon Karas. And I have picked out 36 of my favourites for this double CD, songs with interesting words, simple melodies and rhythms anyone can sing. I think you’ll like them, too.

Some of these songs are a thousand years old or more. They’re sung by children from a primary school near my home in Athens. Like you, they’d probably never heard these songs before, but they had them off in no time at all. I’m fairly sure everyone enjoyed themselves immensely during our rehearsals and recording sessions. The children are accompanied by musicians I’ve been working with for years now. Most of them still young, they’ve helped me keep our Greek musical heritage alive, a heritage of beautiful songs which have so much to teach us about history and how your ancestors once lived and loved.

I hope you’ll like these CDs I’ve made for you. In fact, I hope you’ll love them, young and old alike, and that you’ll play them as often as you can in the classroom and in every household that’s home to young children.

With all my love,

Domna (2007)

A child’s musical initiation began in its mother’s arms in the safe haven of the home. Incorporated into fairytales and sung games, the first easily-understood songs and lullabies served as excellent teaching material, encouraging children to use their minds and their senses, to name, count and sort, to mythicize and demystify the world around them, but also imperceptibly imbuing them with the communal values and practices with which they would be faced – sometimes traumatically – in real life. As the years went by, they would repeatedly hear songs at festivals and celebrations but also as an integral part of their daily tasks, for our age distinctions did not hold and children, too, were present in the workplace. These songs would further their gradual initiation into the world and into adult culture, and children would gain an understanding of the ideological, social and aesthetic rules of their community; of the laws governing work and economics; of living in and alongside nature; of religiosity and a sense of history; and of their own personal and collective identity.

In the context of this open, life-long learning environment, in which official schooling later played a crucial part in later eras, songs – especially when sung and danced in the ritualistic context of a wedding, for instance, or on great festive days, which is to say in the primary spheres in which ideology was reproduced and transmitted – acquired an intensely didactic and paradigmatic character. They taught ‘the right things’ and children were ideal listeners; like an imprint made in soft wax which gradually hardens, this education would stay with them always. Songs imposed models to be imitated or avoided; gender-specific, one set of songs prepared boys for duties public, political and patriotic (which could include military service), while another prepared girls for marriage and motherhood, equipping them to disseminate their community’s ways and morals and to internalize and safeguard the dictates of their society. The facts of everyday experience were filtered through poetic symbols. The lyrics extolled the virtues of bravery by narrating the manly exploits of heroes mythic and historical; of patriotism, by telling tales of self-sacrifice; of ethics, through accounts of punishments; of toil, through doing without; of transcendence, through talk of love. They reminded listeners of time’s cyclical nature by cocking a snook at nature’s relentless tragicomic laws. By hymning the resurrection and rebirth, they declared themselves at peace with death.

As people grew older, above all else they learned to express themselves through music, to listen and to sing, to dance and to improvise. The children’s musical baptism in the traditions of their homeland came on the feast days – first and foremost Christmas – on which they wandered from house to house in bands, singing and playing the carols or songs laid down for the occasion. While the experience of being an individual within a collective marked an important step towards their socialization, having to remember or invent beautiful and appropriate lyrics was both a test of their abilities and an opportunity to employ and show off their talents as musicians and performers. (And seeing as the children had to walk to distant neighbourhoods, enter unknown houses and, of course, earn their first money, it was also a test of courage.) With their well-tuned ear, their virtuosity, their ability to improvise but also to collaborate and perform as part of a team, the charismatic singers and musicians of the future stood out among the young carol singers. It was a hard life, but the best of schoolings…

But all these tests, these relations and meanings are no more. The manifold world of folk song has been rendered simple and fragmentary, with content which is often incomprehensible and references that defy explanation. Schools, conservatories and cultural societies now select those parts of ‘tradition’ they consider worthy of preservation, deliver performances that suit the given time and place, teach their children to distinguish the local rhythms and to dance to them. It’s telling that the only part of the curriculum that addresses anything ‘traditional’ is the gym class. Children are taught a couple of ‘folk’ songs in their Greek lessons, but as written works, shorn of their music, their ethos and their meaning, and, above all, divorced from their cultural context. Because no one has ever considered Greek folk culture worth teaching – to the extent that it can be taught, even as folklore – in schools. And if teachers do occasionally try, they must do so alone and unaided. No one ever asks the children what it is they ‘hear’, what they understand, or what meaning they ascribe to these songs of tradition. Besides, that is, their Greekness.

So let’s call this collection you’re holding an aid for those who want to expose today’s children to stimuli from a world both lost and misunderstood. The first 18 songs are chosen, adapted and performed to be suitable for younger children. Their pleasant and easily-grasped tunes, their easy to remember and often amusing lyrics, their consistently pedagogical nature along with the discrete musical instruments that accompany them, all make for a priceless anthology of traditional music for the children of today and tomorrow. Moreover, the lyrics and the texts accompanying the songs allow parents and teachers to tell their children about the traditional culture that brought these songs into being, about how closely people’s lives were once intertwined with nature, about the jobs that once needed doing around the house, the agricultural or seafaring life, the fun-poking spirit of Carnival, the folk reception of historical events, the local musical and linguistic idioms. Songs 19 to 36 are well-known songs representing a range of geographical locations and the local musical idioms associated with them. There’s a story in each one, if you care to look for it… and I can only hope some children will be inspired to search them out. Luckily for them, they still have their grandparents to help them.

Miranda Terzopoulou (2007)

The Domna Samiou Greek folk Music Association would like to thank Johannes Kärcher for his kind donation.

Also: the mayor of Athens, Nikitas Kaklamanis; Konstantinos Manos and Giannis Demou; the Hellenic Literary Historical Archives and Manos Charitatos; the headmistress of Nea Smyrni’s 9th Primary School, Kyriaki Anastelli; Sotirios Pavlakos, Sivylla Kekridi, Panagiotis Daskalakis, all the parents and students who threw themselves heart and soul into the recording; Niki Marangou, Yulie Papatheodorou, and, lastly, Anna Kanaki and the children of her “Workshop” for their artwork.