00:00

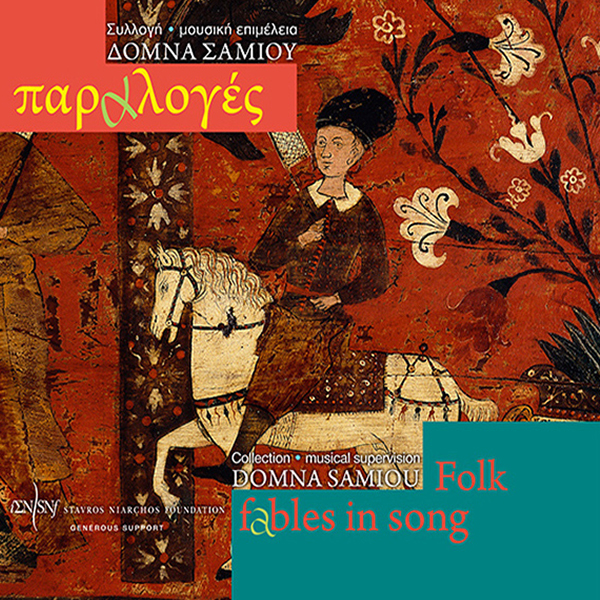

Home / Her Work / Discography / Folk Fables in Song

In fables, fragments of ancient myths are preserved. On this CD, Domna Samiou & her collaborators sing tales of the fabulous and the fantastic combining the real world with the supernatural and narrating stories, often tragic, which might once have occurred – or could do so one day – however imaginative they seem. The CD contains rare and priceless songs with the authentic voices of ‘old people’, which Domna recorded herself in situ.

The songs included date from three different recording eras. Meaning that, apart from the songs my associates and I recorded in the studio, there are others sung by simple folk I met long ago on my travels around Greece.

And though these latter recordings are far from perfect, these songs surely impart more of their singular atmosphere and style to the listener when sung in the authentic voices of the people. Lastly, to give as full a picture as possible, we have also included songs from previous Association releases.

I hope the results will prove pleasurable and rewarding.

Domna Samiou (2008)

And these songs, centuries-old and with everything in them, are what we call ‘fables’. The range of myths, and the inventiveness with which their component parts are added, removed, adapted, transferred, combined and reworked, is staggering. In fact, it is this ongoing process of recreation that has kept these songs fresh down the centuries, kept their tales of sprites and princesses relevant, their kings and viziers contemporary, their Saints George and Turks modern-day foes.

Having grown further and further removed from their historical ‘roots’, these songs serve as musical myths whose subject-matter expresses collective representations. As such, they allow every group and generation to imbue them with new meanings of their own or old meaning they have rendered comprehensible again, and –through their singing– to express the needs of their present.

Along with dirges and Carnival songs, these sung, metrical fairytales lie closest to the point at which the complex outer world of ‘events’ intersects with the dark inner world of desires and fantasies. Which is why fables are sung in a spirit of meditative joy at Carnival feasts, and as dirges lamenting specific or symbolic dead. They are sung and danced in ways revealing the tales which they relate –as slow unaccompanied table songs sung to a monotonous, repetitive melody, or as slow, ritualistic dances at weddings or the great Spring feasts– to teach and bring relief as best they can to the community on those key occasions on which it convenes, remembers, and bonds anew.

Fables were often not sung at all, but recited like fairytales at get-togethers to the rhythms of everyday speech. The audience would have identified with the tragic tales and often wept as they listened. The singers/narrators –folk equipped with artistry, taste, an excellent memory and a knowledge of history, psychology and social rules– had no qualms about intervening in the songs they sang, instinctually matching names, places, secondary narrative strands and details of every sort to their audience’s codes and inner needs. Which is how the songs came to be imbued with new dimensions which would be readapted in perpetuity to every new context in which they came to be sung.

The often extreme events they relate helped listeners incorporate the supernatural into their rational view of the world, and by extension into the irrationality of their subconscious minds. The lack of demarcation between the wild world of exotic lands, plants, animals/creatures on the one hand and the tame, humanized world of livestock, crops and civilized human society on the other helped the audience mentally to bridge the realms of fantasy and reality. And as they gradually came to accept that threatening sprites are an integral part of life, they could also accept as part and parcel of existence those unpleasant, unacceptable, ineffable feelings which can lead to conflict even within the sanctuary of the family; conflicts every member of society had to be equipped to deal with.

Concealed behind their poetic, symbolic language and the fantastical things they describe, the songs actually table painful conditions of human existence: Oedipal conflicts, being deprived of a mother’s love or a father’s protection, incestuous desires, unconfessed hatred between siblings, painful progressions to adulthood, social dictates, materialistic compulsions, ethical dilemmas and ambivalence are all transformed into more or less acceptable realities whose impact is softened by the redemption provided by the dramatic tales sung in fable form over the centuries.

Traditions can exist only as long as they continue to serve and express the interests –communal and individual– of the given social group that embraces and conveys them. An integral part of every aspect of life in traditional communities and equivalent to –or even a substitute for– various social functions ranging from recreation and education to artistic expression, ritual discourse and moulding a collective memory/identity, the songs’ impressive adaptability allowed them to express unwritten social laws and codes, values and fears. And because, as long as people feel the same, they will seek similar ways of externalizing their feelings, they will go on, even today, in certain contexts creating new songs for new audiences on old themes. With their new meaning bestowed on them by lived historical –and arbitrarily imaginary– reality rather than by History, these songs are empowered to express emotional, social and even national tensions, to defuse them, and to cure them with that intangible medicine known as discourse.

Miranda Terzopoulou (2008)

The Domna Samiou Greek Folk Music Association would like tο thank the President and the Board of Directors of the Stavros Niarchos Foundation for their generous donation.

Also: the Benaki Museum and Angelos Delivorias; the Faltaits Museum and Μanos Faltaits; the Society of Euboean Studies and the Vice-chancellor of the University of Athens, Professor Ioannis K. Karakostas; the Ministry of Education and Culture of Cyprus; the Friends of the Music Society (Megaron — the Athens Concert Hall); Efstathios Finopoulos; Charilaos, Frini and Phoebos Papadopoulos; Yulie Papatheodorou; and Michalis Tterlikkas, for his kind participation.