00:00

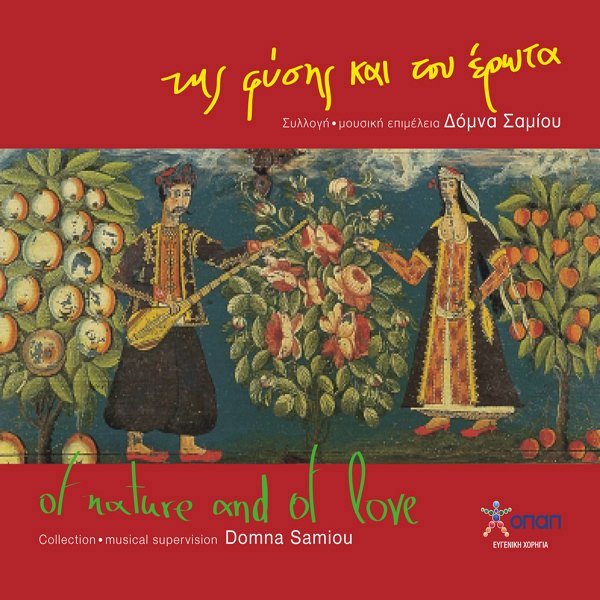

Home / Her Work / Discography / Of Nature and of Love

Through these songs, Domna Samiou pays tribute to how man, in years gone by, worshipped nature as the measure of ultimate beauty, order and harmony, and treated it with awe rather than with the destructive fury of today. The down-to-earth love of nature in these folk songs doesn’t derive from any form of romantic nostalgia; it lies instead in a pure experience of everyday life.

In days gone by, Man worshipped Nature. Then we lost touch with the environment; we became greedy, and Nature came to be seen as an obstacle. And the result is destruction: forest fires, floods, erosion, climate change and other ecological disasters.

I wanted to share a set of songs, therefore, which could remind us of how people used to love Nature and respect their environment as the most beautiful of all God’s creations: from ‘the moon that beams till morn’ to ‘the orchard strewn with daisies’; from ‘the lean, tall cypress’ to ‘the riotous colours of a field of wild flowers’; and –for those closest to our hearts– from ‘my plumed partridge’, ‘curly basil of mine’ or ‘my blooming violet’ (for her) to ‘an eagle’ or ‘mountain torrent’ (for him).

I collected these songs from all over Greece. They span almost every occasion and every season. My admiration for those folk –our people– from whom the songs come, knows no bounds.

Domna Samiou (2006)

Folk songs’ down-to-earth love of nature has a different starting point, a different mode of expression and different content. The feel for nature is strong and vital in traditional rural societies, but more importantly, it is also more profound and more real than any romantic nostalgia. An unforced and often admirable expression of real experiences, it stems from everyday life lived amidst untrammelled nature. That this love of nature is born of life, and stands a million miles apart from romanticism, is especially clear in the kléphtika (brigands’ songs) of mainland Greece, and in the shepherds’ songs of Crete and other islands. But it is clear, too, in so much else; in the root causes, for instance, of the mountain dwellers’ dislike and even contempt for the morbidity of life on the plains so familiar from folk songs.

Romantic love

The Greek people have created numerous myths and traditions relating to romantic love and the full gamut of emotions that accompany it. Popular love poetry has ancient roots, for it is surely impossible to conceive of its absence once a people is present.

The first modern popular love poetry appeared during the final centuries of the Byzantine empire; in the rhymed popular novels of Byzantium, whose plots centre on love, and whose short songs (katalόgia) display all the features of the later style with which folk songs have familiarized us.

These love songs are as numerous as they are fine, and embrace subjects centring on beauty and love’s incandescent passion, on dialogues and short stories of love. This wide-ranging content corresponds to the mass of different (and often contradictory) emotions coursing through the lovers’ hearts, and is often expressed with an admirably epigrammatic brevity and elegance.

Many of these songs of love have a number of verses, though most consist of just a few. There is also a seeming infinitude of two-line works, which form a sub-category of their own and are known by different names in different places: lianotràgouda, manédes, kotsàkia, mandinàdes and patinàdes which, like the paraklausίthyra of the ancients, are sung by youths beneath the window of their heart’s desire.

Since the majority of popular love songs are danced (though not the two-liners), they display a range of metres that extends well beyond the fifteen-syllable line.

What should be stressed and sought out, especially by the young, who are bombarded by models of song that fail to engage their emotions or their souls, is the interest these songs provoke in a contemporary social setting –not as museum exhibits of interest only to historians, but as a living art form, as the substance of our being set in motion, as national oneness– and the invitation they extend to us to evaluate their poetic content, to savour them as poetry, to feel their vibrations in our soul. To take joy from the presence of Eros, sometimes peaceful and tranquil, sometimes turbulent and disruptive, and to accept the songs’ freshness, the plastic grace so perfectly at one with the Mediterranean landscape. To understand that they are part of us, a part of our spiritual, cultural and national roots.

Yiorgos E. Papadakis (2006)

The Domna Samiou Greek Folk Music Association would like to thank: Nikitas Kaklamanis; Sokratis Kostakos, Chairman of OPAP; the Benaki Museum; Angelos Delivοrias and Kate Synodinou; Antonis Matsakis and the Cretan Choir; and Yulie Papatheodorou.

>

>