00:00

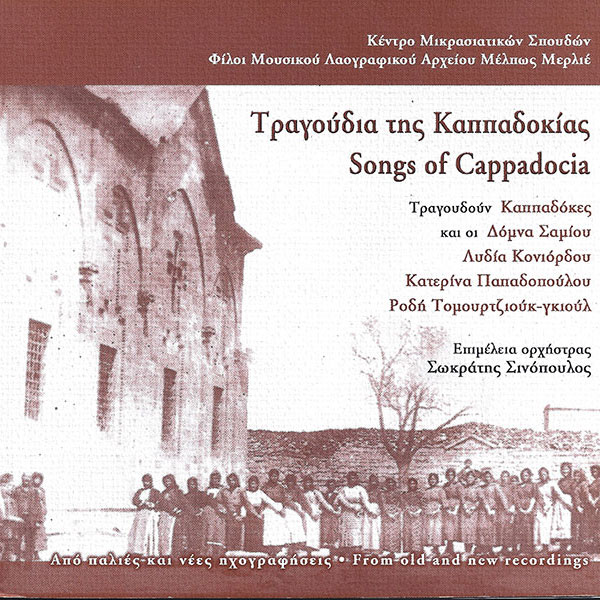

Home / Her Work / Discography / Songs of Cappadocia

Production: Friends of the Melpo Merlier Music Folklore Archives. Fifteen recordings from 1930 with the authentic Cappadocian singers (recording by Melpo Merlier) and twelve new recordings -based on the original- from 2001, with musical supervision by Socrates Sinopoulos.

The following list contains statistical information on the native villages of the above singers. The list was compiled mainly on the basis of data provided by S. Pharassópoulos in his book on Sýlata (Athens 1895). The figures in column 3 show the number of school grades available to youngsters in each village.

Population Greeks Education

Anakoú: 2.800 1.100 6

Malacopí: 2.000 1.600 10

Potámia: 900 800 6

Sinasós: 5.000 4.000 11

Sýlata: 1.100 800 7

Fárassa: 600 585 6 (;)

Floytá: 3.200 2.800 –

The area considered to be Cappadocia today roughly lies within the triangle made by the three cities of Kesária to the north, Ak Sarai southwest of there and Nigdi southeast. In the past the area was considerably larger, extending as far north as the Black Sea. The region was inhabited from ancient times, with the first probable settlers being Hittites. It was in the path of commercial routes to the East and was used by the Assyrians as well as others.

Wood is scarce in this area; therefore the first cone dwellers found it easier and less expensive to hollow out homes in the soft rock. It is evident that one of the earliest Christian communities existed here as Peter, Christ’s apostle, sends greetings to the Cappadocians in the first of his epistles. During the early years of Christianity and in the Byzantine era the hollowed-out cones were often used as monasteries, monks’ cells and churches. Some of the influential leaders in early church decisions came from here as well as two saints: St. Mámas, the beloved saint of wild animals, and St. George, the dragon slayer.

After the settling of Turkish peasants in the region, Greek and Turk lived peacefully together, and, in fact, continued to do so until 1924 when the Greek inhabitants were re-settled in Greece according to the Treaty of Lausanne. These transplanted Cappadocians nostalgically remember their former homeland and many of their offspring have returned to find their ancestral homes. More often than not they have been joyfully welcomed by descendants of their former neighbors.

As with the Pontic Greeks, the Cappadocian Greeks were settled in various sites throughout the Greek mainland -mainly, however, in Thessaly, Macedonia and Thrace- sometimes in existing villages, sometimes in newly created villages to accommodate refugees. They were often ridiculed and treated badly. Many did not speak Greek; for some Turkish had become their first language, but they still utilized Greek in the church liturgy. Not only did they have to overcome the language difficulty, but also endured great changes in climate, profession and life in general.

Traditions also suffered as a result of the uprooting of the Cappadocians. For many their main celebrations had centered around a particular church in their village or region. As they no longer had contact with that particular church there was no reason to hold the celebration. Some dances were performed only on those specific occasions. In time many of them were lost as there was no need for their performance.

Dances and celebrations varied somewhat from village to village depending on the particular feast days which were celebrated. For instance, the five villages in the Fárassa region had two main times when they danced: Άϊ-Vassilis (St. Basil’s day, 1 January) and Easter. The special celebrations in Potámia took place on 3 November (Άϊ-Yiorgi), Christmas and Easter. Indeed, all villages celebrated at Easter, but other celebrations were not necessarily the same.

From Easter to Ascension Day slow circle dances with very ancient roots were performed. Sometimes these dances were known by names descriptive of the formation: Makroulós, long-line; Strongilós, circular; Stavrotós, cross handhold. The steps for most of these were the same, known as Ίsos.

The most popular dance in all the villages seems to have been the karsilamás. The rhythm for this “karsilamás” is not 9/4 or 9/8 as is usually associated with dances of this name. Rather, it is 2/4, accented as quick-quick-slow. If wooden spoons were not available some dancers would accompany themselves with small glasses held on two fingers of each hand and “clinked” together in time with the music.

Although the karsilamás is a couple dance it is rarely danced by members of the opposite sex together. This dance was always performed by pairs of men or pairs of women. Only at family parties would a man if he wanted to, take his wife or his sister to dance. However, neither one should dance very close to the other. It was shameful if a man and woman danced together who were not related in some way.

The slow circle dances were unaccompanied by musical instruments. Quicker dances were performed to the songs by the participants playing the wooden spoons or tambourines (défia). In some villages musicians existed; in others they did not. As in other regions of Greece musicians were hired from neighboring villages when the situation warranted, i.e. at weddings. Sometimes musicians came from other villages bringing their own, instruments.

Today the Cappadocian Greeks and their descendants celebrate in much the same way in their new surroundings as they did in the old. The favorite dance is still the karsilamás, accompanied by wooden spoons, glasses or anything else available. More often today they also have accompaniment from various instruments. In addition to those of their own traditional dances which have remained, they usually dance the “pan-hellenic” dances as well as the local dances of the region.

1. In our musicological commentaries, modes are given in the movable C system, an alphabetical variant of movable do. These modes are to be taken as modulations of the ones playable “on the white keys of the piano”, but regardless of absolute pitch. Needless to say, semitones, tones and augmented seconds of Greek and Eastern music are not equally tempered, nor are they all one standard size each.

2. All directly transliterated Greek words and proper names are to be taken as stressed on the penultimate syllable, unless otherwise designated by accentuation.