00:00

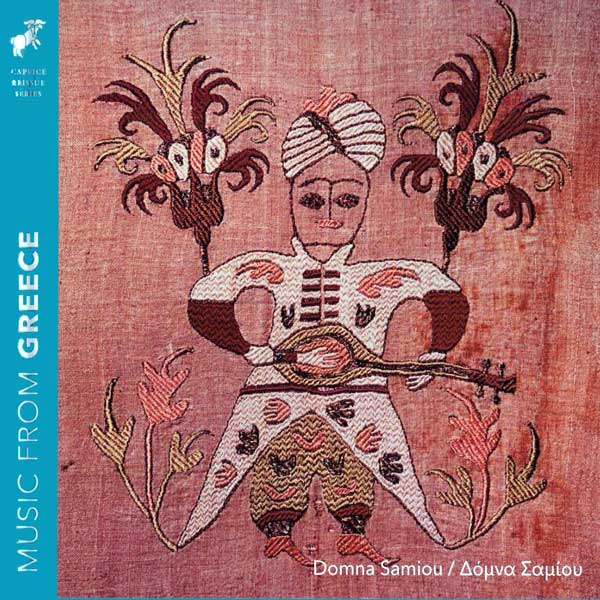

Home / Her Work / Discography / Music from Greece: Domna Samiou

Reissue of the Caprice album Grekisk folkmusik (Ξενιτεμένο μου πουλí) on a CD with 9 extra tracks, and a comprehensively informative booklet about Greek folk music and the woman behind this production – Domna Samiou.

Folk music was never played to be listened to by an audience, in the contemporary sense. It always served and accompanied social events or manual work: enacting magical acts of worship, bidding farewell to those who have died, celebrating the initiatory rite of marriage, raising and socializing children, coordinating and accompanying tasks, strengthening communal cohesion through ritual dances, passing on social conventions and unwritten rules of conduct to the members of the community, preserving historical memory as conceived by the group. No distinction was made between performers and listeners: everyone would sing, everyone would dance, everyone would listen, everyone would judge, everyone would remember. Most songs were local, composed to be sung a cappella or accompanied by a simple hand-made instrument (lyre, flute, bagpipe), and spoke of specific people and events which would have been recognizable to their original audience but grew increasingly indecipherable as the songs moved further away in time and space from the context that gave rise to them. Still, this did not prevent some of them becoming popular throughout the Greek world.

In the vast majority of cases, folk songs were created by anonymous musicians. The words and the lune were passed on orally: each new performance was a recreation of elements which gradually solidified as variations, tried out by multiple singers over time, were rejected or immortalized. The songs moved from place to place with itinerant musicians and craftsmen, with mariners and brides, and in each new area they adapted to their new natural and social environment as well as the local musical idioms, which often closely resembled those of neighboring populations. This is why we find the same songs sung with melodies and rhythms, in different linguistic idioms, even with different references in their lyrics, in geographically distant locations.

We could say that the vast range of local variations evident in Greek traditional music as it has reached us today is inversely proportional to the relatively limited area in which it is encountered – at least now.

It was the awakening of national consciousness in the 19th century – an awakening that was particularly intense in smaller nations, like the newly-formed Greece – that stimulated both interest in folk music and the first research conducted into it. The “nationality” of music had not been an issue prior to the emergence of the philhellene movement and the establishment of the Greek state, when an attempt was made to connect the folk culture – and, by extension, the modern Greek nation – with the civilization of Ancient Greece and thus to establish racial continuity between Greeks ancient and modern. As such, this was both a response to then-contemporary theories presenting the Greeks that emerged out of the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire as wholly Slavified, and an attempt to mould a unitary national consciousness for the Greek people. As was only natural, the ideological criteria adopted by these historians and folklorists influenced the way in which the songs were approached and collected. Songs sung in a language other than G reek, even those sung in the dialects of major population groups (Albanian, Slavic, Turkish) were excluded on principle and would never appear in subsequent anthologies of Greek folk songs. From the very beginning, therefore, the academic interest in folk songs of Balkan Greece, a poor but astoundingly fecund country in musical terms, would have a major impact on that same musical tradition, which remained very much alive. The almost exclusively philological and highly censorial approach to the Greek folk song, a complex cultural phenomenon, and a dynamic process of artistic expression and communication consigned it to virtual obscurity – and this is a country in which oral culture remained the very cornerstone of social reality.

However, the most dramatic change in the history of folk song would be brought about by the phonograph and the record industry, which would record this musical tradition in exhaustive detail, first in Istanbul and Izmir i n the early 20th century, then in the us in the 1920s and 1930s, and later on in Greece.

These early recordings, and especially those made in the us, preserved established tunes and songs in performances featuring authentic singers and musicians – immigrant farmers in the main who had brought their musical experiences with them to America as these had come down to them through the rules of oral transmission.

Nonetheless, the new technology still wrought enormous changes on the material, as lengthy songs traditionally sung a cappella had to be orchestrated and pared down for recording in order to fit onto the few minutes available on one side of a 78 rpm disc. The old saying “songs have 110 master” no longer held true; their legal owner from then on was the professional musician. The anonymous singer now had a name, links to commercial interests and royalties. Moreover, the popularity of the gramophone, and later on the radio, would turn the bearers of the Greek musical tradition, no matter how far-removed they were from the centres of power, into increasingly passive consumers of music, transforming the originality and creativity they originally brought to the folk tradition into imitation and repetition. And a little-known, badly misrepresented musical tradition, which had only survived down the centuries thanks to its instinct for daring renewal and improvisation, came to be weighed down by a millstone of staid conservatism which, while attractive to researchers and rulers, was repellent both to the new bourgeoisie, eager to put their rural past behind them and mainly to a literate, politicized and restless younger generation.

In the years which coincided with the return to democracy in Greece after the junta, some academics and artists sought to change the way in which folk music was received and perceived and decouple it from the vapid picturesqueness it had come to signify following its misuse by the Colonels. Domna Samiou would prove to be the most effective and popular figure in this new wave (her wide-ranging activities are detailed in the biographical note below). Domna was the first person to teach the difference between tradition as high art and tawdry folklore, and she was hugely influential, especially – as time would tell – among the young.

Today, an ever-growing number of young artists who have studied folk music and been creatively inspired by it are proving that “tradition”, that much-abused concept, is anything but dead; rather, it remains a force that inspires and instructs the present. By rejecting the museum and its pseudo-reconstructions, by getting out there into schools and colleges, bars and music venues, Greek folk music has achieved again the position it deserves. And its subtle charm continues to win new converts, even among new and increasingly Western-oriented generations.

Domna Samiou

Domna Samiou’s novel-like life encapsulates the history of Greece in the latter half of the 20th century. Born in 1928, in the shantytown that was, at the time, Kaisariani, in Athens, to parents who had fled the village of Baindiri, near Izmir in Asia Minor, after the events that led to the forced exchange of populations between Greece and Turkey in 1923, she lived her childhood in the inhumane, but at the same time truly human, conditions of poverty and solidarity that typify the lives of displaced people. It was this environment that made her a woman of the people and imbued her with an open-handed generosity. It also provided her with her first musical experiences, which would instill in her a love of traditional music – it was as if this tradition was the only means to protest and resist the forgetting of a lost world, the only way of righting the catastrophe that had befallen her people. Continuing to honour and acknowledge her debt to this lost homeland throughout her life, she would repeatedly declare her respect to the authenticity of the performances by those nameless teachers who moulded her art and her soul.

During the German Occupation (1941-1944) – which would rob her of her father, who died of hunger, and her 20-year-old sister, who succumbed to the tuberculosis which ravaged the city’s poor – Domna was fortunate enough not only to survive by getting away from the refugee neighborhood, but also to be welcomed into the home – indeed, to be effectively adopted – by the wealthy, cultured and art-loving Zannos family, who offered her work, an access to the city’s upper class milieu, along with other types of knowledge, and – most importantly – who, appreciating her voice and her feel for singing, recommended her to Simon Karas, a teacher of Byzantine and traditional music, instinctively helping her to fulfil her destiny.

Thus, at the age of 13, working during the day and attending high-school at night, she had her first educational experience of Byzantine and folk music at the Society for the Dissemination of National Music. It was as a member of the Society’s choir that she would first collaborate with the National Radio Foundation, where she would work from 1954 on. By that time, when the wave of internal migration, that followed the end of the Civil War, made important musicians from every part of Greece to come to Athens, the National Music Department started recording them for its broadcasts; in her position in that organization, Domna would become acquainted with a range of local musical idioms, while simultaneously embarking on her first ventures into researching and supervising the music tor recordings, theatrical productions and films.

Maintaining a formal, rigorous relationship with his students, Simon Karas would decisively mould her knowledge, voice and technique. Still, and more importantly, he would steer her towards research and a moral and intellectual approach to cultural conservation, thus guiding her towards her later, multifaceted career. In 1963, she began her own journeys to the Greek provinces to make recordings on the field and to collect musical material for her personal archive.

The next important turning-point in Domna’s life came during the Colonels’ dictatorship, when she met and began her collaboration with Dionysis Savvopoulos, a talented and ground-breaking young song-writer who was making inspired attempts at that time to break down barriers and combine Greek elements with Western rock music. Greece’s conservative, nationalistic powers – political, ecclesiastical and military, culminating in the military junta – were using the country’s folk music in the most distorting way possible, turning their opponents and young people in particular, against their own tradition in the process. With her appearances, in 1971, at Rodeo and Kyttaro, hang-outs at the time for the adversaries of the regime and its military kitsch, Domna challenged and triumphantly reversed this cultural hijacking, spearheading a huge revival of interest in folk music among young people. During this same period, her participation at the English Bach Festival in London (organized by Lila Lalandi in 1971 and 1973) marked the start of a brilliant career as a performer at major concerts in Greece and abroad in which she revealed the unknown Greek folk music to the world, shattering the monopoly previously enjoyed by the bouzouki.

It was her now dominant career as a singer that led Domna to a different approach to traditional music. Applying the strictest of criteria, she set out to reveal the purely artistic dimension of folk music without, however, underplaying the properties of her own characteristic musical personality. In the unknown songs that she sought and discovered, she was much taken with the oldest tunes, the rarest scales, the slower, more challenging, melodies, because they provided her with an opportunity to give prominence to her vocal identity, to perfect her technique, to demonstrate her virtuosity and explore the rare micro-intervals she enjoyed such mastery of. During this stage in her career, she gathered round her Greece’s finest singers and instrumentalists, experienced musicians and newcomers alike, along with ethno-musicologists eager to question the givens about Greek folk music till then. Acknowledged as both a singer and a researcher, Domna was respected for her prodigious talent but also for her dedication to the cause of traditional music.

In 1981, she founded the “Domna Samiou” Greek Folk Music Association with the aim of “preserving and promoting traditional music and, above all, releasing records and organizing events in accordance with strict academic and qualitative criteria, far from the demands of commercial companies” By the lime of her death, the Association had issued no less than 20 CDs, DVDs and LPs.

In 1994, Domna began to teach folk singing at the Athens’ Museum of Greek Folk Musical Instruments. In October 1998, the “Megaron” Athens Concert Hall organized a monumental concert-tribute to mark her 70th birthday. And while she was a favourite of the music-loving public, her work also earned numerous awards, culminating in her awarding by the President of the Hellenic Republic, Konstantinos Stefanopoulos, in 2005.

Surrounded by collaborators and students, friends and supporters, Domna kept up her publishing work until the end, overseeing, too, the organization of her unpublished personal archive and its digitization and uploading onto the Internet. Thanks to associates, old and new, the www.DoinnaSamiou.gr website continues to grow, while high-quality publications continue to be released, always under the supervision of the Association, with which our company collaborated creatively for this album too.

(In the context of her international appearances, Domna Samiou undertook her first tour of Sweden in 1979, giving a number of concerts accompanied by dance performances by the Greek Folk Dance Group “Eleni Tsaouli”. She also recorded the LP, Xenitemeno mou pouli, which was first released in 1980. Sixteen of the pieces on this new album are taken from that first release. The rest, along with some of the photographs, were kindly provided by the “Domna Samiou” Greek Folk Music Association. Our heartfelt thanks to the Board of the Association, and to Tasia Papanikolaou and Jasmina Stanojevic for their valuable assistance.)

Miranda Terzopoulou was born in Athens. She is very familiar with many regions of Greece, having traveled, studied and recorded events and manifestations of popular culture – traditional music and folk rituals, in particular – around the country. She has worked with different ethnicities, linguistic and religious minority groups, both within Greece and beyond. Through recording and filming all that she needs for her research, she has assembled a significant archive of rare audio-visual material.

In collaboration with Caprice Records, she has prepared an entirely new material to accompany the re-release of the Domna Samiou 1979’s recordings, which were initially published in 1980 on LP, under the Greek title Ξενητεμένομουπουλί [Xenitemeno mou pouli/My heart-sick bird flown far from home]. She has enriched the album with new tracks from the Association’s archive, looked for new photographic material, written commentaries on all the songs, along with introductory texts, and updated the presentation to take into account the four decades that have passed since the album’s initial release.